Robert Roth

The Rage of Aquarius

For Gerald Williams.

Robert Roth and Herb Perr

You can print this page by copying its URL to printfriendly.coM.

“Invest yourself in everything you do. There's fun in being serious.” – John Coltrane

1.

Herb Perr died the last day of 2018. Herb was an extraordinary artist with a deeply subversive consciousness and an out there personality that could create instant community every time he walked down the street or into a room. In mid 2019 Hands Up, Herbie!, a graphic biography of Herb written by his son Joey Perr made its appearance in the world. All the words, except for the introduction, are Herb's. Using pen, paper and photoshop all the illustrations are Joey's.

First in the spirit of full disclosure and total transparency, every word written here is written with great love for Herb, one of my very closest and dearest friends. I also have great love and admiration for Joey, who I have known from the moment he was born.

I even make a cameo appearance in the book. I feel very flattered by that. And very proud of it. As does And Then, a magazine I co-create with some friends. And which Joey, Herb, Joey's sister Rosa, and Joey's mother Mimi have all appeared in over the years. There is also a reproduction of a piece by Joey, a combination of words and image published in And Then when he was eight. All this adds to my fierce attachment to the book. An attachment I first felt when Herb told me with great excitement about the project that he and Joey had embarked on a few years before his death.

Over three years he and Joey would get together and record Herb talking about his life, a wildly creative complicated life. The pain, anger, insight, humor. The raggedy edges of Herb's life remain intact. Nothing is smoothed over. We watch how that life unfolded. Herb, always vivid, deeply self-reflective, unfettered by expectations of what he should and shouldn't say. A great story teller. And Joey? With the subtlest stroke of the pen, he can capture the most complex and deepest of emotions.

Joey in the introduction talks about being the target of his father's flashes of rage. At those moments Herb became his own father. Something he very much didn't want to be. Joey wrote, “Growing up as he did at the mercy of his father's volatility, his own flares of parental anger, his own short temper, made sense now. Raising his own kids, he's been trying so hard to avoid the trap of re-enacting my grandfather's spasms of rage. If he sometimes came up short, it wasn't because he wasn't trying.”

Throughout his life Herb carried the devastation his father Jerry inflicted on Herb's mother, sister, two brothers, and himself. He was part of a world of Jewish gangsters living in Brighton Beach, hustling for a living, hiding from creditors, starting fights in the streets. A small time bookie, a person filled with fury and violence, a need to be a big shot. He shot two people in Miami when he lived there for a while. The police thought the people he shot were bad people and didn't arrest him.

Herb said, “So this was my father's reality. Violence was the thread that ran through my father's life.”

I once spent time with Herb and Mimi in their country home. They were both under tremendous stress. Just before I arrived they were thrown smack in the middle of a very serious devastating family emergency. Suddenly Mimi's mother, embedded in Mimi, would flash out at her, and Herb's father would flash out at him. The two would clash. Then Mimi and Herb would re-emerge and negotiate the damage. It was deeply upsetting being there. Also moving and profound was how they cared for each other as they navigated such treacherous terrain in the shadow of a lurking tragedy that no one should ever be faced with.

*

Long lean muscles, very thin, for a period in middle age, almost emaciated. Exceedingly strong and super competent. He was like quicksilver. Non stop over the top energy. He had built a huge loft space all by himself over the D'Agostino supermarket on Greenwich Street in the Village. It had been an empty space, and he convinced the owners to rent it to him for a very cheap rent and that he would transform the space. I once painted the roof silver with him years later. This was to reflect the sun to prevent the absorption of heat into the loft. I still have a photo of us in our painter hats, arms draped over each other's shoulders. Totally swept up in his energy, I did do my bit.

For years Herb's loft was the hub of much political/cultural ferment. And at times, more than at times, personal drama. Social gatherings. Political meetings. Demonstrations organized. Movements born. Cultural events. Far ranging discussions. Lectures. Slide shows. Birthday parties. Book launches. Concerts. Huge New Year's Eve blowouts which later morphed into New Year's Day all day brunches.

I remember one time an artist from Germany giving a talk about his trip across the country. He described winding up in a jeep or an SUV filled with people guzzling down whiskey as a drunk Ted Kennedy drove around the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port at over 100 mph.

Many people from all over the world would visit. Different people would live there over the years. Ronnie Gilbert, who sang with the Weavers (The Weavers singing "Goodnight Irene") then later toured the country with Holly Near, stayed there for a while. As did the brilliant writer, social critic Sohnya Sayres who moved there from her single room occupancy on MacDougal St. Liberated from her tiny apartment with its single hot plate into this vast new expanse of a loft, Sohnya went into a cooking frenzy making a dinner consisting of seven main courses and 18 desserts for six of us.

It was on Herb's roof that I saw the final rehearsal of a performance piece he, Irving Wexler, and Robert Landy were about to perform at Franklin Furnace.

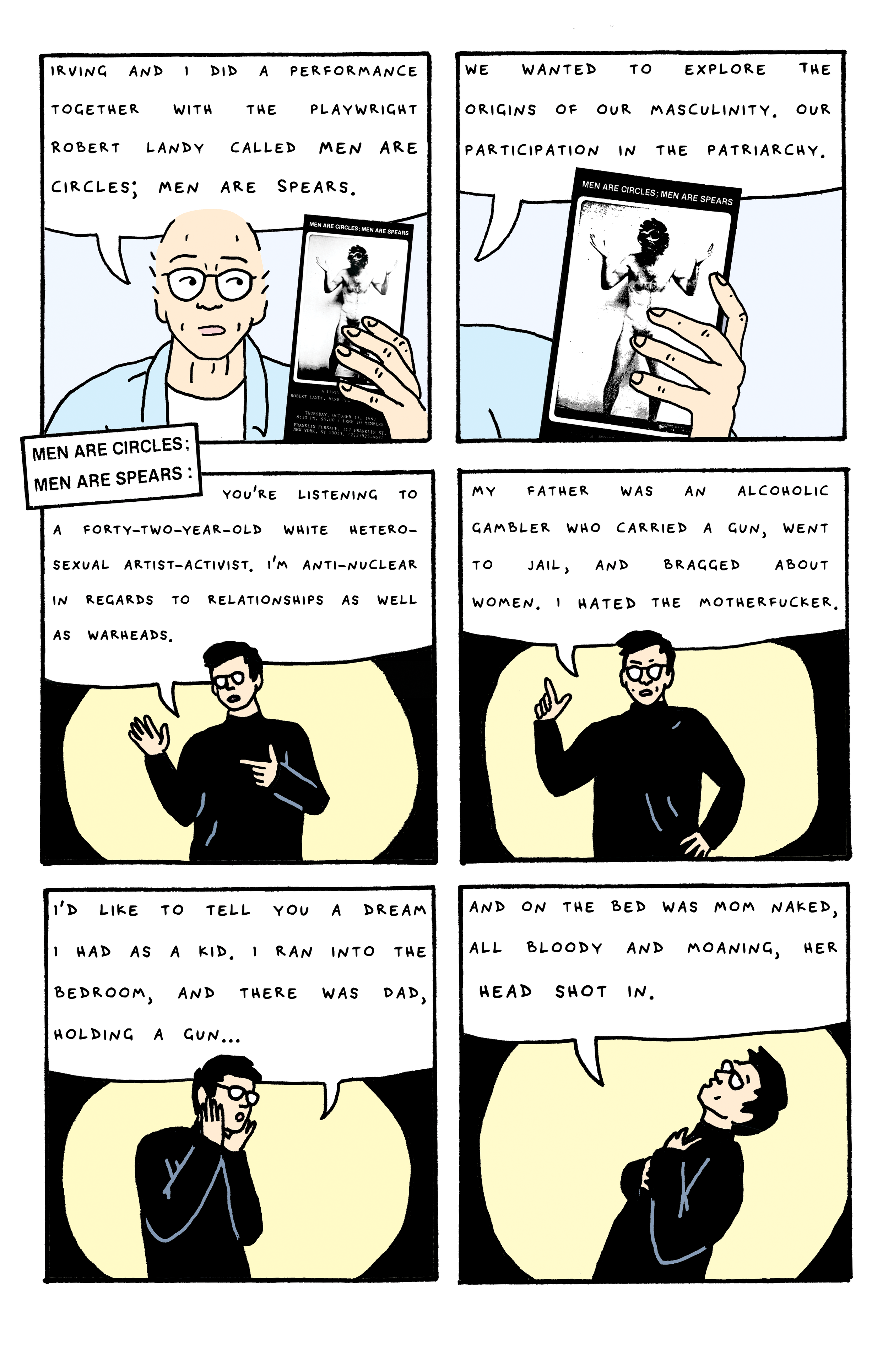

“I wasn't interested in agitprop, and neither was Irving. I didn't like that type of thing shoving it down people's throats. Let other people do it. They did it better than me. What I wanted to do and what Irving wanted to do was performance art. Irving and I did a performance with the playwright Robert Landy called Men are Circles; Men are Spears. We wanted to explore the origins of our masculinity, our participation in the patriarchy.”

A number of years earlier Herb had moved away from the mainstream art world where he had been a young, rising star. He told me one important feature of making it in that world would be to spend his mornings networking, making connections, solidifying contacts, nurturing friendships. He also spoke of the subtle types of sexual negotiations, often oblique, hinted at, at times acted on. His work was bought by big time collectors, he had gallery shows at the Whitney, and other museums bought paintings of his for their permanent collection.

“I was able to get through because I met these successful artists. Established artists like Helen Frankenthaler who was my undergraduate professor at NYU. I didn't know who Helen was at first. I didn't know that she was famous. But I liked to ask questions, and she liked me immediately.”

Sometime later.

“I knew Frankenthaler was a Democrat, but I was not. I was much more radical. I didn't talk to her about the Marxist study groups I was in. I knew it wouldn't work. There was one time she asked me for help in her studio because David Rockefeller was coming that day. He wanted a big painting for his vacation home in the Caribbean. David Rockefeller was an amiable guy. He picked out his paintings, and we all talked about them.

Here was this big, wealthy, powerful guy who represented capitalism, and I was getting involved with all these socialists and Marxists.

When it hit him how sordid the mainstream art world was, he dramatically pulled away from it. The gallery that sponsored him dropped him when his painting style changed. Collectors complained that those changes devalued the work they had bought.

It was here, during the Reagan years, as his own awareness expanded, that he began to focus more sharply on the deeper injustices in the official art world as well as the society as a whole. He joined other artists struggling against racism, misogyny, homophobia, and class contempt. As well as the US war machine and imperial domination across the globe. Of particular focus at that time were the crimes committed by the US in Latin and Central America. As well as the Caribbean. Much work was also done opposing Apartheid in South Africa.

As part of an alternative, insurgent, politically vibrant, radical art world, he and some friends started PAD/D (Political Art Documentation/Distribution). “We expanded our outreach to performance artists, visual artists, and critical theorists.” It was there he met Irving Wexler. Lucy Lippard, who had been the driving force in the creation of PAD/D, wrote a beautiful foreword to this book. Irving Wexler had a larger-than-life personality. Dramatic and intense. He was warm and outgoing. But way too often also extremely sour and overly critical. Like Herb, he had a deep communal impulse. He liked people. He also liked complaining about people. Like most of us, he was full of multiple contradictions. His, though, were writ large. He was more than twenty years older than Herb and me.

I remember one time Joel Cohen, known also as the Sticker Dude, close friends of the three of us, brought Irving and me to a Grateful Dead Concert at the Long Island Coliseum. Joel was a sought after presence at many Dead Concerts where he had developed a following of his own by producing and freely distributing—to one person at a time—Grateful Dead inspired stickers. On the way home Joel's car broke down. After a long wait, Joel along with his car got towed into the night. Leaving Irving and me stranded at a gas station in the middle of what felt like nowhere. A professional boxer who was hanging with a couple of friends worried about our safety and escorted us to the nearby LI Railroad station. Suddenly, spontaneously, Irving in his 70s, who had been a boxer at Brooklyn College, and our new friend started shadow boxing on the platform. There we were, 2:30 in the morning, the two of them bobbing and weaving, throwing phantom punches under the ghostly station lights.

*

I stood in the lobby of Franklin Furnace, watching as waves of people entered. The intensity, the electricity, the anticipation of the audience. Friends, comrades, colleagues, relatives, total strangers. The room was filled to capacity. Robert, Irving, and Herb each had their own following and everyone seemed to know that it was important for them to be there.

Strange the things you remember. I said hello to Ruth, an old lover of Irving. I hadn't seen her for quite a long time. You could feel both her excitement as well as her trepidation. I know she felt Irving had jilted her for a younger woman and still felt bitterness about it.

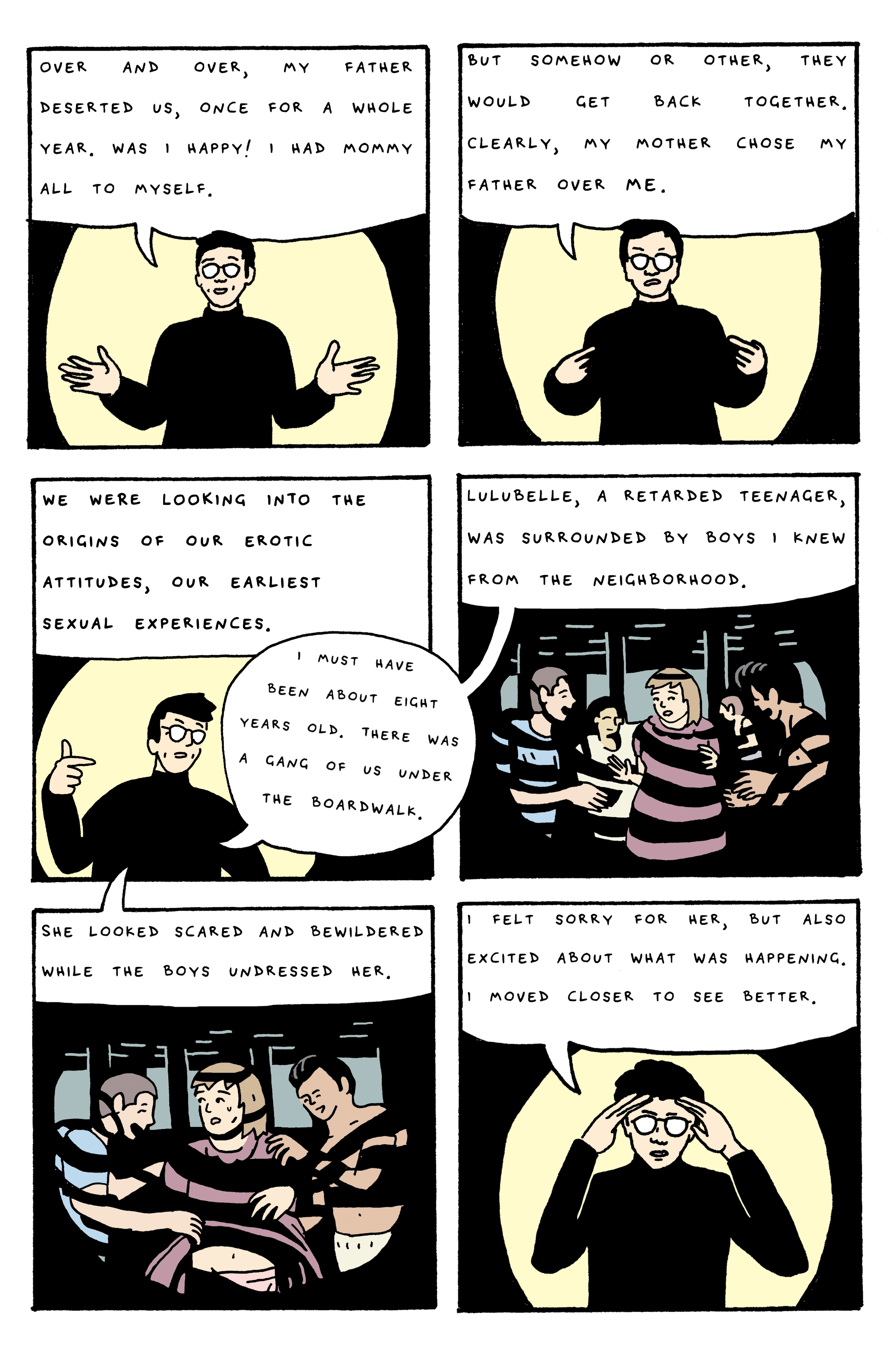

Raw, vulnerable, deadly serious. Going deep into themselves. Their painful histories. Their childhood traumas.

Herb, Irving, and Robert mixed individual monologues with three-way banter. It was all out there. Family madness, childhood trauma, ways in which they had been betrayed, ways in which they betrayed others. Their sexual fantasies. Their sexual needs. At one point in the performance, my friend Madeline Artenberg reminded me, they discarded all their clothes and were totally naked on stage.

A monologue of Herb's reproduced in the book:

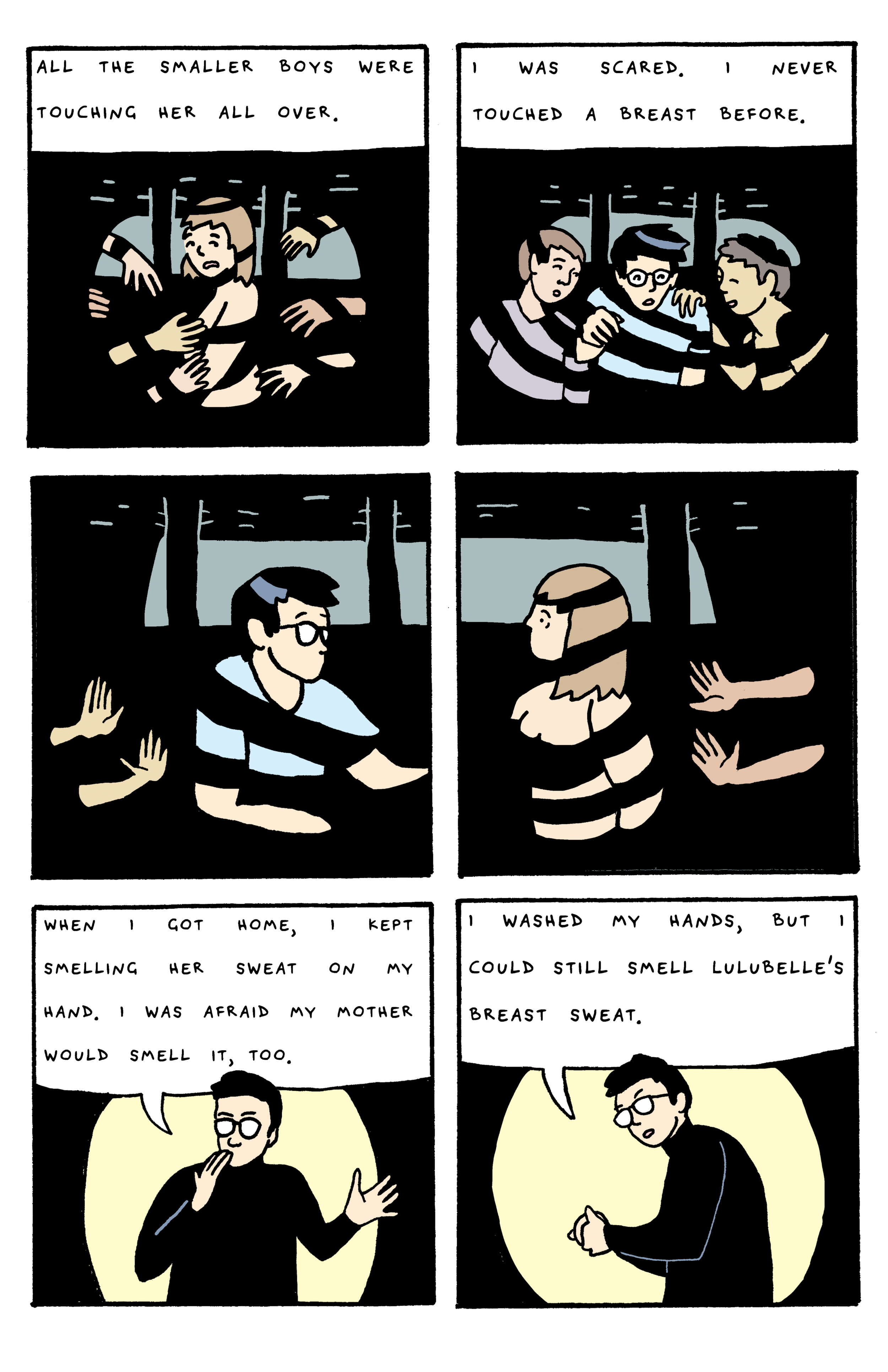

We were looking into the origins of our erotic attitudes, our earliest sexual experiences. I must have been about eight years old. There was a gang of us under the boardwalk.

Lulubelle. A retarded teenager was surrounded by boys I knew from the neighborhood. She looked scared and bewildered while the boys undressed her.

I felt sorry for her, but also excited about what was happening. I moved closer to see better.

All the smaller boys were touching her all over.

I was scared. I never touched a breast before. When I got home, I kept smelling her sweat on my hand. I was afraid my mother would smell it too.

I washed my hands, but I could still smell Lulubelle's breast sweat.

Joey's illustrations here are terrifying, riveting, and profound.

Lucy Lippard wrote a full page review of the performance for the Village Voice. Every word of which jumped off the page.

There was some thought that Men are Circles; Men are Spears could be performed around the country. But for reasons I don't remember, they weren't able to.

Recently I was speaking to Sohnya about the performance. She reminded me that she had been recruited to play a bit role in it. When Herb finished one of his monologues, Sohnya called out from the audience. “Poor baby, poor baby” with “the meanest cynicism I could put in my voice.”

*

At Herb's funeral, Joel and I were the only two people who I recognized from that radical art world period of his life. A couple others were at the shiva. His friend Perry was from the era right before us. Perry told me he didn't see Herb all that much during the PAD/D period. Though clearly they remained close friends. I would on occasion run into them at galleries or on the streets of SOHO. They were always pretty hilarious together. Two live wires feeding off of each other. I always carry copies of And Then with me. Perry would always buy one. Something I deeply appreciated. In recent many years Herb and Perry would see much more of each other.

Perry Gunther:

I met Herbie in grad school. It was a course in American art. He did a paper on ? and I did mine on Frank Lloyd Wright. I sat on the left side of the room up front. He sat further back to the right. We were the only two men in the class. So we would catch each other’s eye. It was the late sixties. I was married, living in Park Slope, and he was single, living on Chambers Street. He brought a different girl each time he came to my house for dinner. I resented being used as a date destination. But that was partially out of envy because the sexual revolution had begun, and it seemed he was having all the fun.

Later, when I moved to the Bowery, he lived in the west village. We were both making art looking for a gallery and dreaming of success. The sexual revolution was in full swing. Herbie was the mischievous one and I was more recluse, the dreamer. Think “Children of Paradise.” But we fed off of each other. I knew he needed me as much as I needed him. We did not know the that a bond was forming between us that would sustain itself for a lifetime. After losing contact for some ten years we met on the street in Kingston NY. Herb had married Mimi and had two kids and I had married again. I thought, “How did I ever lose contact with Herbie?” Our friendship picked up for the second time. Now both of us with more life experience watched each other age and grow wiser.

Years passed and suddenly Herbie became fatally ill. It was easy for me to take for granted that we would share many more years together. Close to the time of his passing, I lay with him in bed and we talked about the days he played basketball for Lincoln High School in Brooklyn. I felt his failing energy, and I wanted to crawl inside him.

I still call his name when a memory from the past appears.

Throughout Herb's life, he gravitated to spaces that he felt could liberate him from the confines of whatever world he was presently immersed in. As a kid, he left home at 14. Each step along the way he was curious, open, filled with anticipation, determination and a hunger both for contact and a desire to make an impact on the world. He threw himself headlong into each new environment he entered. But always maintaining an ability to scramble expectations and put his own particular mark on things.

As a junior, he was captain of the Lincoln HS basketball team that made its way to the finals at Madison Square Garden. As a senior, he quit the team and joined the art squad.

“But the art squad, that's what I loved. These people were on the fringe of the social scene. They were more interesting. Some of them were gay, some of them spoke funny. They were shy. They were intellectual. They had all kinds of ideas…. And they liked me. They elected me head of the art squad. And I liked everybody. I was just taking everything in.”

At the playground, Black kids from Coney Island would come to the neighborhood to play football and basketball. “And at the end of the night these guys would sing a capella to us.” Older kids, psych students from Brooklyn College, would come by. While the players were resting, they talked about Sigmund Freud and the benefits of therapy. Young Herb took it all in and decided he needed therapy to deal with all the turmoil in his life. He looked through the yellow pages and at random picked a woman who turned out to be a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. She charged him 25 cents an hour. She became like a surrogate mother to him. She became good friends with him and invited him to spend time with her and her husband in their country home. And through her and her connections she got him an art scholarship to NYU and from there entrée into the mainstream art world.

In the section called Larry, Herb spoke about a close friend from the playground who also had a major impact on his life.

“There was a guy who played basketball with us, Larry, who was a pederast. He was twenty years older than us, but he was well liked. We became very good friends. Of course he tried to come on to me many times, but I always told him 'Forget it.' He would take us to see theater at night. We'd see the first Beckett plays on the Lower East Side. He would take us to see Count Basie in the jazz clubs. I heard Joe Williams sing at Birdland. Then he'd take us to that place in the Village where Dylan Thomas died a few years before. We'd all get vodka and whiskey sours, and we'd come back drunk and feeling great. Like he wasn't violent or anything. The guy was really smart. He really introduced a lot of music and culture into my life. He bought me a winter coat, this guy. And he knew everyone in the park. Everyone knew who he was, but nobody cared. It wasn't like he was violent or anything. There were some kids who probably liked seeing him and having sex, but it wasn't my cup of tea. It was all part of the Brighton Beach scene. You know what I mean.”

*

One day Herb asked me to come with him to a picnic in Prospect Park where someone named Mimi Bluestone would be. A writer, a musician, a deeply engaged political person, Mimi at the time was an editor of Sing Out, a magazine started by Pete Seeger. In recent years, she has done seriously important work about the environment.

On the way home from the picnic Herb asked, “Do you think she likes me?” “Well yes!” I answered laughing.

Meeting Mimi brought Herb into the last major very long epoch of his life, which later included the birth of Joey and Rosa and everything that came after.

When Mimi and Herb started living together it significantly changed the time he and I spent together. I remember the feeling of liking someone as much as I did Mimi while simultaneously experiencing a dramatic shift involving the nature of my contact with Herb and its impact on my everyday life.

Their wedding took place in the Village loft. Both Herb and Mimi had a misplaced confidence in my ability to follow instructions. I need to fill out forms multiple times before I get it right. I had to sign the wedding document as a witness—it was such a beautiful looking document—but I almost signed the line that Herb was supposed to sign as the groom. Multiple hands grabbed mine just as I was about to do it.

*

Economic insecurity, psychological violence, physical violence permeated the early part of Herb's life. The toll on the family was devastating.

For long periods of time Herb had to pull away from different family members. At times seriously hurting them in the process. He had to distance himself from them in order to survive. Over time he got closer to his two brothers and could more fully appreciate both their struggles and their achievements.

When I was younger, in fact all through my life, but really mostly when I was younger, I could put real hurt on people. I was afraid I would be sucked into their world. Trapped. Feel judged. Confined. Insulted. Not treated seriously. Not understanding the full force of my own personality and my ability to be taken seriously enough to hurt someone else.

This isn't easy. Because even when someone else is barely holding on, they can channel the most virulent negative, severely oppressive cultural bound attitudes that they themselves are suffering under and turn them against you. You can get totally sucked into the other person's world. Trapped. Your energy depleted. Your feelings of inadequacy intensified. Feel there is no real way to escape. I have a close friend that I argued bitterly with when we were younger. Some of the issues were real. The disagreements could be ferocious. Years later we would speak and I would flash out at him. Imagining him saying something that he hadn't. It was only a day later when I reflected back on it that I realized that he hadn't said what I thought he had said. I was arguing with a shadow presence from long ago. Sometimes you are arguing with yourself. The other person representing one part of a debate raging inside you.

Of the many painful stories involving Herb's family, those about his sister Susie are among the most searing. Susie and Stuey, the two youngest of the family, were essentially left alone to fend for themselves as kids. Susie was the baby of the family. Seriously neglected. She was dangled out into the world with barely any protection. Both she and Stuey became strung out on drugs. Susie spent her life hustling for money. Scamming people. Going into prostitution. Feigning accidents and then suing. She lived with a man who continually humiliated and exploited her. She periodically called Herb, often in the middle of the night, hitting him up for money. Their mother Helen always complained to the others that Susie was trying to take advantage, trick her out of money, wheedle something from her. At times actually worried she would be assaulted by Susie and her friends. She would get Herb, Stuey and Victor all worked up, but then guiltily slip her money. Near the end, Susie kept devolving, spinning into an endless hell. Her body ravaged with illness. At one point, living with her boyfriend became unbearable. She was quite ill and wanted to move in with Helen. Herb's younger brother Stuey who had once been hooked on pills had by that point become a drug counselor. He said the family had to stop enabling her if they ever wanted her to get better. That only by hitting rock bottom could she start rebuilding her life.

Well, she hit rock bottom and died. A horrible, horrible, horribly painful death.

“On the one hand, you can understand why we all behaved the way we did,” Herb said. “But on the other hand, how horrifying this was for Susie; all these rejections from the time she was a child until she died.”

2.

For years I would attend seders in Herb and Mimi's apartment in Park Slope. Joey and his sister Rosa would always be there. I have known them since they were born and love them dearly. Friends of Herb, Mimi, Joey, and Rosa would be there also. The age divide at this point is basically people in their 60s and 70s on the one hand and people in their 20s and early 30s on the other. I just turned 76.

I sometimes wondered what Rosa and Joey and their friends (not together since most went their separate ways) did after the seders. Their nights often just beginning while mine (after a long subway ride) would be coming to an end. To a person all their friends are serious, thoughtful, engaged in the world. They certainly are not clones of each other. Just as Mimi and Herb's friends aren't clones. Far from it. But the broad arc of how we take in the world is similar. There are also obvious differences. The associations we have, the things that brought us into consciousness are different. As well as the nature of our struggles. The people we generally spend our lives with. The ways we yearn and search for meaningful contact. The assumptions which we operate out of.

When I was in my 20s, I was friends with the great short story writer Meyer Liben, who was at least 30 years older than me. One time we both spoke about making up baseball teams to help put ourselves to sleep. When we started talking about those teams, the players were totally different. Each reflected the players of our childhoods. In fact, every player he mentioned I never heard of.

The last seder I attended, a year and a half before he died, Herb spoke to Rosa's friend Jane Stiles and me about the three of us doing a video together. Jane and I never really spoke at any of the seders. But her sensitivity, consciousness, magnetism, and talent were palpable.

Over the last few years, Herb started to make short videos. Making them even as his health began to crumble. I appeared in one where under his direction I read a poem of mine. Another filmmaker Michael Szpakowski incorporated what we did into a larger video. Hendrik van Oordt composed the music. Lotte van den Dikkenberg-Methorst performed it on the piano. Herb and I collaborated on other things over the years. I'm not much of an actor. I've been in some films. All for friends who made major allowances for me. Still within the extreme limits of my talents, I did okay in them.

When Herb made his suggestion, I was even more excited than I showed. I think, I don't think, I know, the three of us could have pulled off something special. But Herb was ill, and Jane was very busy. It probably would have taken three more seders for it to happen. But still …

Herb's health crashed horribly, and he died. The launch of Joey's book was both an occasion of celebration and acute pain. Herb's protracted illness and death were devastating. When Jane walked in we hugged. I blurted out, “We never made our movie.” She said something comforting and then told me of two films she had made and acted in and sent me the link to them both. Both are as good as I knew they would have to be. Both take place in what needs to be described now as the pre-pandemic world.

Much of One Eye Small takes place late at night. At a burlesque show, then at a crowded dance party in an art gallery. Certainly it could have been the destination of any number of my younger seder-mates. The movie itself is poignant, comical, and serious as two women, Elizabeth (played by Hani Vital) and Irene (played by Jane), accidentally meet and negotiate a space of new contact. Allowing the night to take them wherever it will.

Jane's other movie Dom is about the [friendship, relationship] between two women.

One's name is Dom (played by Annapurna Sriram), the other (played by Jane) is Beth.

The movie begins with Beth in a doctor's office in Chinatown. She is in the grip of pervasive sadness, has stomach cramps and difficulty moving her bowels. The doctor asks if her boyfriend treats her well. A millisecond hesitation; she answers yes. She then picks up the herbs prescribed for her.

We see Beth next, walking down a street in Chinatown. She peers into a door. And leaves. After a few steps, her friend Dom calls after her. They haven't seen each other for a while. They go to Dom's apartment in the building Beth had peered into. Both Dom and Beth light up the screen. Beth, light skinned, blond, is alternately shy and bold. Dom is taller, darker, with thick wavy brown hair. She is outgoing and vibrant. Their friendship goes way back. Maybe to college, maybe to high school, maybe to elementary school.

In the apartment we see Dom put little plastic envelopes filled with pills into a bag. Next Beth and Dom lie on Dom's bed, passing a joint back and forth. Beth looks at Dom with a sensualness or an intimacy or a deep need for [intimacy, contact] that maybe borders on desire. It is a look to my everlasting pain and frustration I can easily misinterpret. Their shoulders and bare arms touch. Dom suddenly says she has to go off to work and jumps out of bed. She asks Beth to join her.

Playful with a bit of an edge, Dom seems to enjoy getting a rise out of Beth. Making her a bit of a co-conspirator, Dom talks about having lunch with Beth's mother just the week before. She said that her mother gave her $200 to go to the herb guy because she thought Dom was depressed. Beth laughs and says he doesn't cost two hundred dollars. A bit later Beth asks what did you say you did for work. Dom says she told her mother that she worked as a DJ. Beth laughs again.

Dom's customers are all [Latino, Hispanic, Latinx] men. A kind of fluid intimacy passes between them and Dom. When I delivered newspapers, once a month I would deliver a theater newspaper to various theaters and acting schools throughout the city. Quick, intimate, warm exchanges. The theater people to a person were all embracing, dramatic, electric, outgoing, instantly intimate and a lot of fun. My heart would skip a beat multiple times on the route. Thought of them each as 30 second romances.

Here it was not newspapers but pills and money, warm smiles, and quick kisses. One [customer, client] gives Dom a donut, which she savors with a dramatic flourish. Showing off to Beth [the perks of the job, the good vibes of the gig, the sweet communal flow of the streets, the appreciation for the service she is providing, the general warmth of the people she interacts with independent of anything]. For some reason she doesn't offer Beth a piece of the donut but totally involves her in the pleasure she is having in eating it.

Dom and Beth ride bikes as Dom makes her rounds through lower Manhattan. Dom then almost dances on her bike as they ride over the bridge into Brooklyn. Both are incredibly graceful, their energies in sync. Are they in some stoned state of grace or just simply lost in the power of each other's mystic? From a distance, they look like young teenage girls. Up close women in their late 20s.

On the other side of the bridge they get off their bikes. Dom lights up a joint. Beth bounds up right in front of her. Face to face, they pass the joint back and forth. Hugging Beth tightly, Dom declares, “I am a bad influence on you. If anyone hurts you or breaks your heart, I will fucken kill them.” Beth pulls away and tells her she doesn't want her protection. But even more to the point, it is an expression of Dom's own vulnerability and precariousness. She approaches the world with a bravado continually fluctuating between false and real.

The very next scene. They wait in a vestibule. A man (played by Sean Avery) comes down and says to Dom, “Sweety, you're late.” He totally ignores Beth and gestures with his head for Dom to come into the building. She looks resigned, a bit distressed, tells Beth to wait for her as she follows the man into the building. The bounce in her step is gone. Beth seems concerned as she looks through the glass part of the door. Dom's legs grow heavier with each step as she walks up the stairs. The man's hand firmly on her lower back as he climbs up behind her. In the credits he is called Creepy Dude.

Is she going to have sex with him for money? Is he her supplier? Some combination of both? Something entirely different? She doesn't want to be there. But for some reason she wants Beth there. Possibly as a witness whose very presence might represent one of many conflicting voices [playing out, shouting] in her brain.

Beth waits a long time for Dom to return. First in the vestibule, then out in the street. At one point she starts to cry. For herself? For Dom? Maybe just overcome with the basic sadness that she spoke about to the doctor.

When Dom returns, Beth asks, “Who was that man?” A pause. “Do you need money?” Dom shoves her away and snaps angrily, “Grow up.” Beth then grabs her, pushes her and suddenly forcefully, passionately kisses her on the lips. Dom shoves her away again. They both fall back against a wall, standing there collecting themselves. Silently [negotiating, feeling through, allowing] the moment to settle. Their day continues. Throughout the movie there was an [intimacy, a kind of manic escapism, a surrender to experience] [embracing, avoiding, surrendering to] every day loneliness, pain and at least for Dom economic need. A connection, a push pull, growing out of that need. As well as a genuine profound openness to the world and to each other.

Near the end of the movie, Dom and Beth wind up on a beach in Brooklyn. It could be Brighton Beach or Coney Island. (Interestingly, the last scene in Hands Up, Herbie! takes place on the boardwalk in Brighton Beach.) Dom grows deadly serious. She talks with both anger and grief about seeing a tiny baby shark caught by a fisherman thrashing, gasping for breath on the boardwalk as people looked silently on. Within a couple of minutes the shark dies. The fisherman then throws it into the ocean “as if it could survive out there.” Dom just keeps shaking her head, unable to say another word.

At night when day ends, will each be flooded by the small and not so small humiliations of the day? Or will adrenaline, desire, friendship, love, surges of emotion, possibly sex, ride over that pain, dissolve it, keep it at bay?

3.

Pandemic. Here in my isolation, old age, death hovering nearby, every day bleeding into the next. Catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror. Look almost ghostly. I see my knees in a full-length mirror. They are old man's knees, flesh folding over them. My face more gaunt, wrinkles on my neck. I drool a bit now. I feel a wetness slightly dripping from the side of my mouth. I am falling apart in real time. I feel cut off from a vital flow of humanity. Entering an old age cut off even from myself.

Equally painful is the divide I feel from my younger self. During the shutdown my sexual senses have virtually disappeared. And my aging body feels like an abstraction even as I can feel it shutting down.

One of the most haunting sections of Hands Up, Herbie! is Herb discussing his relationship with painter Mark Rothko. Helen Frankenthaler and Robert Motherwell invited him to Provincetown. Herb was Bob's assistant for five years. “I knew how to mix his colors, how to paint for him. Of course I just painted where he told me to. He was worried about his assistants taking too much credit. I painted on his Elegy to the Spanish Republic series, which he had started in 1948.”

Helen and Bob asked if Herb could drive Mark Rothko, who was there recovering from a heart attack, to a teaching gig at a nearby school. Herb drove Mark back and forth for the entire summer. Rothko was in the grip of a terrifying depression. He was grim, insecure and bitter. On their rides home he would say, “These people don't respect me. They ask me questions. They don't listen to me. I don't think they like my work.” Herb said that Mark lived not far from him, and “he would come to my studio to watch me work. He loved that I would always have people around. He liked watching the young people. If I had parties, he'd always come to the parties, sit in the corner, and watch everybody. He was this little overweight guy with thick glasses sitting in the corner.” At the end of the summer, to express his gratitude, Mark offered Herb a painting as a gift. Herb replied that he drove him out of friendship and didn't want any kind of payment. “[I] was a schmuck, because he had wanted to give this to me as a token of his appreciation, not as payment. I didn't know how to accept a gift and he may have been offended.” A few months after they returned to New York, Mark Rothko killed himself.

His name has come up three times since I started writing this. My friend Dave told me his mother loved Rothko's work and had a collage made of postcards of his paintings hanging in her kitchen. Recently I read an article about someone visiting the home of a higher up in the People of Praise, the anti-abortion, homophobic Christian Community that Amy Coney Barrett belonged to. Right there in their living room was a huge painting by Rothko. She described feeling intimidated by the wealth and power that such an expensive painting represented.

And finally another friend, Marlene Nadle, told me when writing at the Village Voice, that she knew that the paper's cartoonist Jules Feiffer and Mark Rothko along with about twenty others signed a letter to Lyndon Johnson opposing and supporting others opposing the war in Vietnam. This was the liberal humanistic artistic community at its very best. The tension between that world and the alternative radical art world Herb left it for is a compelling one.

*

Diane DiPrima died a few days ago.

Summer 1960. I was visiting my cousin who lived on the Lower East Side, later called the East Village. I was sixteen at the time. He brought me to Diane di Prima's apartment where a group of people were reading poems not of their own but from books. Poems from years, decades, centuries before. Diane had this explosive energy. Celebratory, intense, commanding. There were huge paintings of people having sex on the walls. Later we ran into Leroi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka. It was raining lightly. He was wearing an olive poncho with the hood covering his head.

*

About fifteen years ago Michael Kranish, who was a manager at a public housing project, one night saw a Puerto Rican security guard sitting in his booth reading my uncle Sandor Voros's book American Commissar. The book is about my uncle fighting in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. It was published in the mid 1950s. There might be only 10 copies of the book left in the world. Somehow he got hold of one of them. And there he was 60 years later reading my long dead uncle's long out of print book.

I told this story to my friend Bob Perron whose novel The Blue House Raid about the 1968 raid by North Korean commandos on the presidential palace in South Korea just came out. He looked up my uncle's book and saw that it was digitized. I remembered my cousin's son had digitized it a few years ago. I sent the link to a few friends.

Bernie Tuchman responded: Thank you Robert. I went to the final chapter and epilogue. It is a stirring conclusion. Sandor’s story is that of a man of great intellectual as well as physical courage. Those are the qualities that gave him the strength and integrity to be a maker of history, revealing himself to himself in his response to the pressures he faced. One cannot expect a more meaningful life than that. I look forward to starting from the beginning and receiving the story as it unfolds.

*

Tom O'Horgan was the director of the rock musical Hair which was first performed on Broadway in 1968 It was a raucous alive celebration of the counterculture, sexual liberation, racial justice, the anti-war movement. Sex, drugs, and the heralding of the arrival of a new tomorrow.

I met Tom a number of times many years later. He was directing different operas by my close friends Margaret Yard and Michael Sahl. He had a glorious huge loft in Manhattan. The walls were covered with musical instruments from around the globe. Many from centuries ago. As well as posters from plays he directed. He also had a short story in And Then, “Sibling Lust,” about two brothers who wind up having sex with each other.

During the summer of 2008 there was a revival of Hair performed in Central Park. Mainstream commentators spoke glowingly of it. The city came alive with its energy.

When the moon is in the Seventh House …

(The 5th Dimension singing "Aquarius")

Here it was 40 years later. Once again heralding the arrival of a glorious new tomorrow.

All the while Tom's health was rapidly declining. He had serious dementia. He had been moved from New York into a nursing home in Florida. Isolated from all those who cared about him. Separated from all those who loved him. Disappearing, being disappeared, totally hidden from the outside world. Tom O'Horgan, alone in the nightmare of what had become his own tomorrow. He died just a few months later in January 2009. What the hell do you do with that?

*

Shulamith Firestone, very early on in our friendship, told me more than once, that the moment they teach her book The Dialectic of Sex in women studies programs it would mark the defeat of the women's liberation movement. In fact, in her mind, the very existence of women's studies marked the end of any possibilities of revolutionary change.

All these years later they not only have been teaching her book for decades, but recently her family donated her papers and art work to Smith College. Unfortunately her extraordinary quilts had been destroyed by mold as a result of a flood in her brother's basement. They understandably feel this provides a treasure trove for scholars who are doing serious research. The image conjured up in my head is that of a young woman filled with curiosity and passion, joining Shulamith's soul spirit, thinking deeply about the issues that Shulamith has written about.

It is a tension that keeps playing itself out. Where do powerful ideas and revolutionary disruptive ideas get co-opted, diluted, absorbed, used to fuel and legitimize institutions that reproduce power. Even the most militant and radical work becomes just a part of the cultural machine. All the while the subversive impact of the work is enough to subject it to ferocious assaults from reactionary forces that are well organized and relentless.

Women studies, Black studies, Puerto Rican studies, environmental studies. Important work, serious books and documentaries, organized movements of resistance grow out of these institutions. They help wake the consciousness of people who then run with it and do enormous good. This is true even if it is only one's own sense of the world that is significantly altered.

But what made Shulamith Shulamith is lost forever.

Shulamith, James Baldwin, Arnie Sachar, Carletta Joy Walker, Myrna Nieves, Fredy Roncalla, Muriel Dimen, Howard Pflanzer, and Ralph Nazareth write brilliantly about social, psychological, economic, and cultural forces. They describe stark structural realities with insight and sensitivity. They in different ways talk about the psychic need for those structures of oppression to exist. They also describe the psychic terror of the oppressor. Where that need to dominate and obliterate springs from. And the lengths they will go to protect themselves from confronting their dread.

*

Writing this piece grows more unsettling as I go along. At 76 would I be like Mark Rothko in the pre-pandemic world of Jane's movies. Craving to be near that energy. Soaking in the creativity. Alienated from it, drawn to it. Pulled into the chaos. Merging with the intensity there.

Joey's book brings me face to face with my own mortality and the possibilities and maybe even the likelihood of a terrifying, debilitating illness. I keep thinking of the people who I have loved who have died very painful deaths. I am also flooded with the beauty, struggles, and massiveness of the lives they lived. As I continue writing I keep spinning out, going wherever this is taking me.

Hands Up, Herbie! brings Herb and Irving Wexler vividly alive again for me. I am enormously grateful to Joey for that. How could someone who had enormous impact like Irving disappear almost so completely once he dies? He died October 20, 2001. Friends now rarely mention him. He was a basic presence in many of our lives.

Well now that I have Irving here with me, I want to stay with him a bit longer. This was a eulogy I delivered at his memorial service:

Often when people give eulogies what they are saying about the other person is what they secretly wish would be said about themselves. Albeit under better circumstances. And so the wonderful things I want to say about Irving Wexler are really the wonderful things I want said about myself, the wonderful things he made me feel about myself.

He made me feel passionate. He made me feel compassionate. He made me feel that my life mattered and that it mattered deeply. He appreciated my written work, affirming it and understanding it in ways few people have. He made me feel as if my words had a special significance. He made me feel that I had great analytic gifts and a deep sense of poetry and powerful political commitments. He made me feel that I was a person of enormous sexual power or at least a person of enormous sexual wishes. He made me feel beautiful. He made me feel each time we met, each time we spoke, each time we did anything, each time we argued, something important and historic was occurring.

I could say he made me feel elegant. But that would be stretching things. But Irving in fact was elegant. He was dapper, rakish. He had a real sense of style. He was also funny, funny in the way people with larger-than-life personalities can be funny. For he had the writ large, comic presence of unfettered genius.

Often when Irving would enter a room a field of energy would surge towards him. However sour and critical his disposition would be just seconds before, and very sour it was likely to be, he entered a room like a superhero from the cosmos, totally delighted to see anyone and everyone. His enormous capacity to appreciate and delight in people in the end was stronger than his disappointments and what to me, at least, was his overly critical disposition.

I visited Irving shortly before his death.* To see him in his hospital bed, his own world shutting down just as the outside world was entering into its new stage of cruelty, was excruciating for me. Yet inside the magnitude of the present horror I looked at him and felt a strange comfort.

We live. We die. We live and we die. And to think that I was placed on earth at a time I would meet Irving Wexler filled me with gratitude.

* Herb was with me when I visited Irving this last time.

I think again about my friends. I knew many of them when they/we were the same age as the characters in Jane's movies. They had the same raw shimmering energy. They were alive with curiosity, commitment. Stunningly beautiful in the myriad ways people can be beautiful. At times frozen in pain. Other times wildly alive. Some like Dom always living on the edge, having to scramble to make a living. Some wound up on SSI. Some went crazy. Others got all caught up, sucked into long tangled professional careers. Others were freelancers working all hours of the day and night whenever they could get a job. Others could barely, if at all, make ends meet. There was much personal devastation as well as serious moments of transcendence. Movements, major, major movements were formed by some of them. Radio broadcasters. Filmmakers. Musicians. Writers. Political organizers. People living their lives in many forms. I delivered newspapers and for a while was a janitor. The fiction I wrote when I was in my 30s was about people straddling an alternative, insurgent radical world and a mainstream world they were seriously, significantly, militantly in opposition to. Yet in some serious, often unexamined ways, still a captive of. Living lives both of resistance and compliance. Constantly [facing, working through] its tensions and contradictions.

The characters in Jane's movies are similar. Though in the ways we meet them they are less overtly political than those in the world of radical artists that Herb was a central figure of. They clearly aren't “apolitical.” They have social, psychological awareness that is fully woven into who they are. What would they be doing now in the midst of the pandemic? How would they be making a living? Would they be out in the streets joining the social, political upheavals happening everywhere. How safe are they? How is their health? My concern and affection for them—yes even as fictional characters—exist outside the confines of the movies they're in.

I think of them and hope they are all okay.

Earlier in speaking of One Eye Small I said some of it took place at a burlesque show. That was how it was described elsewhere. Yes. That is sort of accurate. What I didn't say was that the performers were in drag. Because I didn't know if that was the right word to describe them. Or more importantly how they would describe themselves. Transgender and non-binary, gender nonconforming, gender fluidity—words continually shift as consciousness shifts with it.

As I write this, the news is filled with trans women of color being assaulted and murdered. There is also a huge mobilization of people protesting these assaults. There was an article in the Guardian talking about the history of resistance led by trans women of color, going back even before the Stonewall. Highly politicized, they are there in the forefront of resistance.

Another article written by a trans man about joining a high-end sports club. His anxiety about being there. His need for the acceptance of the other men. He has observed and studied male behavior ever since he was a child.

How are the performers in Jane's movie similar or different than the political trans activists written about? And in what ways does it matter? If at all. And what if they aren't? Do they exist outside attempts to put someone else's label on them? Refusing to be hemmed in. Defined. Re-defined. Or are they actively, defiantly, proudly lending their voices and power to the surge of liberatory energy filling the streets. God knows if I were 13 or 14 or 19 or 23 or 27 or 56 where I would be. Who would I be? How would I be?

Maybe next time around I will find out.

*

There were many overlapping worlds at Herb and Mimi's wedding.

Herb's father had already died. Herb's older brother Victor was there as well as his younger brother Stuey. Herb's sister Susie was not there. Rosa and Joey were not yet born. But it is hard to imagine any such event without them being a part of it. They keep popping up in my memory as if they were there.

Up from Florida, Stuey and his wife would be in New York for a number of days. I remember them sitting at a table in the loft searching for various narcotic anonymous meetings to organize their stay around.

Herb's mother Helen was there also. A member of gamblers anonymous, she was a strange mix of grit, resignation, depression, and humor. A humor that would literally throw me off my chair when Herb quoted things she said in the book. In many ways she was beaten down. By her husband, by the society. But certainly not beaten into total submission.

In different forms the weight of misogyny came heavily down on both Mimi's and Herb's mothers. Both were seriously depressed for huge chunks of their lives. Both also had engaging and powerful personalities. There was a consciousness divide, a class divide, a cultural divide I can't fully describe between them.

Mimi's mother Edith was super politically conscious. But maybe to the point of having her ideas and understanding of the world too well ordered, too tightly formed.

Veterans of decades of political struggle, I would see her and Mimi's father Harold marching at demonstrations. There was a rhythm and beauty and intimacy between them as they marched and chanted their way through the streets. We would wave to each other with big smiles on our faces. But in those last terrible many years of her life, Edith descended into a massive paralyzing depression. In Hand's up Herbie! Herb talks about his own mother's depression that only lifted to some extent after Jerry, her husband, Herb's father, died. She had been in the grips of depression as long as he could remember. As a young boy there would be days that she couldn't get out of bed. Herb also described often going to bed hungry.

I could really be off here. If so I apologize to everyone. Helen seemed to feel somewhat out of place. The wedding reflected a socially and politically aware progressive consciousness. But that was not going to stop Helen from claiming her space. These words are hard to write. Because in this context my description of the wedding can sound like a back-handed compliment. A sort of put-down. But it isn't. But the tension there, I can be projecting like crazy here, is I think an important one. I feel Herb was a bit embarrassed, worrying his mother was coming off as something like an urban country bumpkin. But it felt more like his own class anxiety was surfacing. His whole life he had to navigate different worlds, worlds he never was fully at home in.

In Hands Up, Herbie!, as well as Dom and One Eye Small, there is a continuous struggle for dignity among all the people you encounter. Jane and Joey reveal this brilliantly in their work with such tender insight and sensitivity. In very different ways, almost everyone we meet experiences the world as “outsiders”: artists, political organizers, radical theorists, gamblers, sex workers, bookies, hard core Jewish gangsters, an ancient broken down former hitman, people hooked on drugs, people selling drugs, people doing alternative forms of Chinese medicine, sexual exiles, athletes, musicians, kids hanging out, Holocaust survivors, immigrants, refugees.

For some this led to profound moments of awareness. For others it doomed them into lives of severe anguish. Some did extraordinary things. Others very destructive things. Mostly it was people up against it, navigating the world as best they could.

I think I will stop here and give Herb the last word:

On the positive side my father was a great raconteur. He was a very well-liked bartender because he was very friendly with everybody. He had a good sense of humor. He'd always tell jokes. One of the things I got from him, which is very good, is that I love to talk to strangers. He'd talk to everyone, no matter who they were. So that aspect I liked about him. I learned from him not to trust authority figures. Unlike the other fathers in Brighton Beach, my father wasn't part of the system. He taught me to suspect the system…. If anything it moved me to the left. Protesting the war. Not afraid of authority. Questioning authority.

I learned from my father's irresponsible gambling. It brought my father down, made the family unhappy. But like him, I wasn't afraid to take a chance. Throughout my life I took chances. Changing my life. Meeting people. Making art. Not buying into one way of thinking.

In making art, you're really gambling. You're making something. You're not sure if it's right, if it will work or not. You have to live with the ambiguity, and I grew up living with ambiguity and uncertainty. In survival mode all the time. So I diverted, and I modified everything he was and made it into my own.

Robert Roth is author of Health Proxy (Yuganata Press, 2007) and Book of Pieces (And Then Press, 2017). He is also co-creator of and then magazine since 1987.

All rights to this story are retained by the author. Thank you for allowing its publication on this site.