Richard Federico

Forgotten Riot—May Day, 1970, New Haven Green

Back to the future.

On Thursday, April 30, 1970, the State of Connecticut went on alert in preparation for the May Day Rally at the New Haven Green. My National Guard unit, the 242nd Combat Engineer Battalion, was among those called up by the Governor for that fateful weekend. It became the scariest day of my life.

To put May Day 1970 in historical perspective, it was a perfect storm for protest. The nationally covered murder trial of Black Panther leader Bobby Seale and the “Chicago Seven” was underway in New Haven and President Nixon’s decision a day earlier to expand the Vietnam War by invading Cambodia fueled the fire. The two stories filled front pages nationally at the same time anti-Vietnam War protests, student strikes and civil rights riots were in the news daily.

The “Free Bobby Seale” outcry, along with a crowd stunned by the shocking invasion of Cambodia, spurred the size and ire of Rally protesters. Less than three days later, Ohio National Guardsman killed four unarmed students in what would become known as the Kent State Massacre. It traumatized the country and provoked America's first national student strike, closing hundreds of campuses. In its aftermath, the May Day Rally hardly made the news. All eyes turned to Kent State. But the riot on the Green was a shot away from being Kent State. I was among an armed squad of 11 men standing on a street corner at the Green, a block from Yale’s campus. We would come close to changing history. Thank God we didn’t. Here’s my story:

On the afternoon of April 30, my National Guard unit called me at work and said to report to the armory by 6pm; our battalion was being activated for a weekend protest in New Haven.

As weekend warriors, as we were called in those days, our unit was ill-equipped and minimally-trained. My unit had practiced riot control formations during an extra weekend a month for about a year prior to May Day 1970. The monotonous training took on new meaning when our truck convoy rolled out of Stratford, CT to head to Southern Connecticut State University’s campus in West Haven for a night’s sleepover before heading into downtown New Haven early morning May 1. Our 250-man battalion was assigned to guard high-risk areas, such as utilities, transportation centers and liquor stores.

We left the university campus to head to downtown New Haven promptly at 7am. My memories of our sleepover at the campus are few: sleeping on the floor of an empty classroom filled with 34 sleeping bags laid side-by-side; shaving and showering in a vacant girls dorm; and having the ABC-TV “Eyewitness News” team’s cameras greet us as we assembled in the campus square. By 8am. we were standing in formation in combat gear on a downtown street in front of Southern New England Telephone Company headquarters.

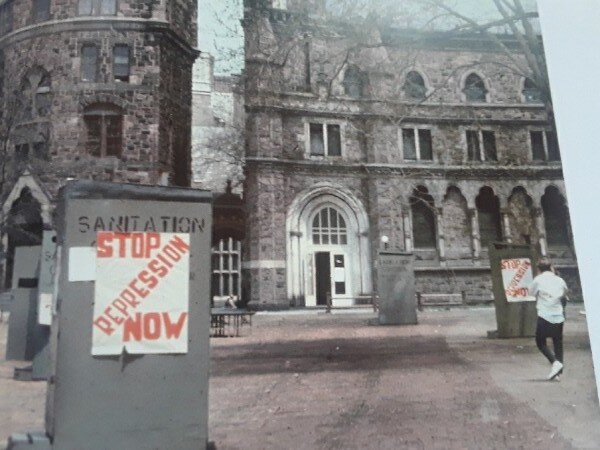

The building was a few blocks from the Green, within walking distance of the Yale campus’s ivy-covered buildings. None of us had a clue what was going on other than a very brief briefing before we left Stratford. The morning hours brought mobs of protesters heading past us toward the Green, shouting obscenities and spitting our way as they walked past our 34-man platoon. We were standing directly in the sun. May Day seemed more like July Day, 80s by noon, our fatigues wet with sweat.

As the crowds filtered by, the verbal abuse escalated. Black Panther supporters mixed in with hippies, peaceniks, anti-Vietnam War protestors and Hells Angels bikers. The dress of the day reflected the bizarre styles of the era, including Afros, striped bell bottoms, headbands, peace signs and tie-dye shirts. Both girls and guys wore their hair long and straight. “Free Bobby Seale” signs and shirts were the street sales of the day.

Bobby Seale, chairman of the Black Panthers and leader of the Chicago Seven, led the rioting at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where Mayor Daley’s cops gained notoriety for their head-banging of demonstrators. Seale supporters felt his four-year jail sentencing had been too harsh. He became a folk hero, an icon for protest, his New Haven trial national news.

We had been given strict orders to avoid conversation with the protestors and take whatever spewed out of their mouths. Although most of us in the Guard were college kids who had dodged the draft and opposed the war, our uniforms were the same as the regular Army. We were Nixon’s guys in the eyes of the protestors. It was getting scarier by the minute as we stood in formation, M14 rifles to our side.

Not all protestors cursed and spit. Some tried to start conversations, but we weren’t allowed to respond, to tell them we sympathized with their views. By May 1970 all the draft-age guys attending the Rally knew they would likely be off to Vietnam, even Cambodia, soon. The war was at its peak. They had good reason to protest; their wives and girlfriends did, too. I empathized with them. My wife was expecting our first child; a riot in New Haven was the last place I wanted to be.

Marijuana and beer further fueled the protestor aggressiveness. As military and state police helicopters made constant flyovers, we could hear the crowd noise three blocks away. Rumors ran rampant. We were told Yale had opened its doors to provide support to the protestors in the form of first aid stations and food. Reports also said Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin—the two most radical spokespersons of the era—were among the stream of speakers that stood on a stage at the Yale end of the Green. Years later I learned Hillary Rodham, a Yale law student, headed a committee that supported the protestors.

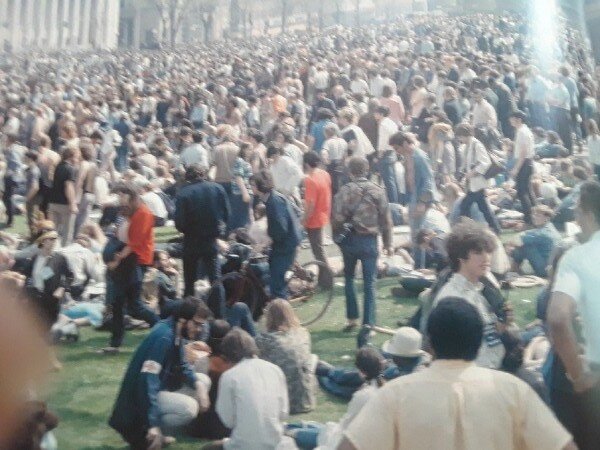

By late morning the weight of our fatigues, helmet, canteen belt and shouldered M14 rifle had taken its toll. I was sunburnt and exhausted by late day. The rally had turned into a drinking and pot-smoking party. At dusk, the crowd of 20,000 began to scatter. Our turn for rest came. Cots had been set up in the telephone building lobby. Sleep lasted thirty minutes. A sergeant’s scream called us to order. The crowd was getting hostile, he said. Each eleven-man squad raced to a street corner that surrounded the Green. We were supposed to back up the local and state police, but they were nowhere to be seen.

Communications with National Guard officers was nil, our scatterbrain squad leader’s walkie-talkie inoperable. There we stood at the corner of Church and Elm, diagonally across from the Courthouse, not knowing what to expect. I was petrified.

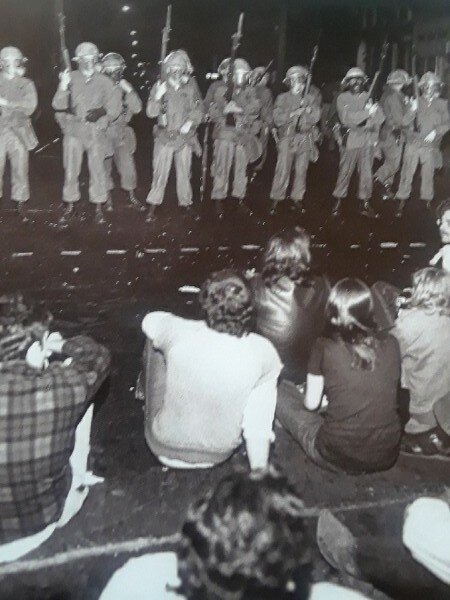

We were in full combat gear—helmets, rifles, sheathed bayonets, gas masks and 20 rounds of ammo. Our squad leader ordered us to span the width of the street in a line formation. It was dusk. We were close enough to the Green to make out the mob a hundred yards in front of us. A rock band was playing at the far end. Sleeping bags and tents dotted the grounds. The hungover raucous crowd was having fun. With dark came fireworks. Smoke mixed with the sky, making it nearly impossible to distinguish how many protestors were out there.

One whacko paced back and forth in front of our line, cursing President Nixon, the Pentagon, the military, Congress, and threatening each of us face-to-face. For the first time, my knees started to shake. Then things happened quickly. We could see panic on our squad leader’s face. “They’re heading our way,” he shouted. “Don your gas masks! Unsheathe your bayonets!”

I took my eyeglasses off so I could get my mask on. It hadn’t been fitted for my prescription. Big, fuzzy blotches of white—the flashlights mob members carried—were moving toward us. My knees were now shaking uncontrollably, death staring me in the face. They were within 100 yards. I grabbed one of the two tear gas canisters I had stuffed under my fatigue shirt. I figured throwing one would come next, then the order “lock and load” would follow. But neither took place. Temporarily blinded, I was literally in the dark until the other guys in the squad started to cheer. A handful of state cops, donning gas masks, and holding billy clubs had stormed out of the nearby Courthouse. They gassed the mob and ruthlessly banged their heads, scattering them. It was over in five minutes.

In two days the Kent State Massacre would become one of the biggest U.S. news stories of our time. On that 1970 May Day weekend, the riot on the New Haven Green came within minutes of becoming the first Kent State. Instead, it became a forgotten moment in time.

Visit the author’s blog at https://richfederico.blogspot.com. Major published works: Battling to Be the Best: Why Companies Compete for Best-Place-to-Work Lists; Op-Ed article in New York Sunday Times; Memoir, Within a Mile of Main Street (Bridgeport, CT); Wine-lovers article, Connecticut Magazine; three CNBC-TV appearances; Also, Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives (Merritt Canteen). Author for Forum of World Cultures.

Rich has published two books under the Riccardo Cordileon Collection: the novella Emerald Dress Seduction; and the novel Why Me, Nadine. Click on them for eBook availability, pricing, synopses, and previews.

This story previously appeared as the Ninth Writers SALON of the Forum of World Cultures.

All rights to this story are retained by the author. Thank you for allowing its publication on this site.